heironymus bosch and the weird little creatures he paints

a look into renaissance artistic trends

Okay, so instead of studying for my Italian final that I have tomorrow, over the past few days I have accidentally fallen into an art history rabbit hole. I’ve watched a lot of video essays, but one that has really stood out to me was this one about Hieronymus Bosch’s painting The Garden of Earthly Delights. I thought I’d give you my own little analysis of Bosch’s life, the artistic-religious trends of the time, and then a look at the creatures in the painting itself, which I find particularly fascinating. There’s a lot here, so let’s get started.

Not much is known about Hieronymus Bosch’s actual life, but I’ll do a quick summary of what a Google Search plus the video essays I’ve watched have told me. He was born Jheronimus (or Joen, depending on the translation) van Aken, which translates to Jerome in modern English, in a Northern Dutch town called ‘s-Hertogenbosch (commonly shortened to Den Bosch). He later changed his name to reflect his birthplace, going by Hieronymus (which still means Jerome) Bosch. Although it is not known when he was born, we do know that he was a Renaissance-era artist, so it was probably sometime in the mid-to-late 1400s. He was a pretty successful artist at the time, growing up in an artistic family; his grandfather was also a painter, as well as a few other men in his family. Sometime in Bosch’s early adolescence, Den Bosch was rocked by a pretty catastrophic fire, which can help explain some of the gruesome imagery used in his works. He joined the Brotherhood of Our Lady, which was a devotional fraternity of sorts in his adulthood, which was an extremely influential sector of the Catholic Church in the Netherlands. He married a woman a few years older than him in the late 1400s and moved to land that his wife had inherited in the nearby town. Bosch died in 1516, as documented by the Brotherhood’s records. This is about all that is known about the painter. There is little documentation of his training or life, as there are no surviving diaries or letters that could help historians to unpack his personality and imagination. There is one drawing of him (seen below) that may not have even been done during his lifetime but is widely considered to be a self-portrait of Bosch in his late sixties.

Den Bosch was primarily a religious town, with almost 90% of its inhabitants working for the Catholic Church. Bosch is no exception. Being a member of the Brotherhood of Our Lady, he is assumed to have had a good social standing and was well respected as an artist. Many of his paintings reflect religious imagery and were most likely commissioned by the upper class for their homes or for the Church itself. During the Renaissance, there was a resurgence of religious iconography being depicted in paintings, ranging from da Vinci’s Last Supper to Carivaggio’s David and Goliath. Depictions of Heaven and Hell are starting to come to life during this period, and some have contributed this to Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy, which reimagines Hell into a nine-circled landscape, but that is a whole topic for another time. Renaissance art, in general, was more naturalized and realistic, focusing on humanism as a style, which is a major distinguishing factor from Baroque art, which is typically more ornate and illustrious. Another major detail about Renaissance art is the background development. You’ll notice in the Bosch painting I’m about to show you how the background is just as detailed as the fore and midgrounds. However, in this particular painting, all aspects can be seen as pretty disturbing or highly sexualized, not something normal for the time period, but something characteristically Bosch. As I said before, the fire in his town may have caused some trauma, which led to a hyperactive imagination, resulting in this vivid imagery, but that is all just an assumption.

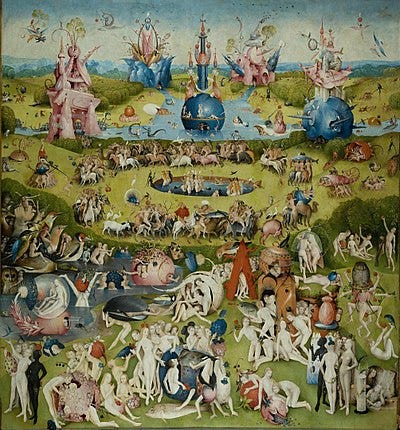

Okay, so let’s take a look at the painting itself. The Garden of Earthly Delights is a triptych oil painting on an oak panel. It’s pretty big, measuring about 7 ft by 12.5 ft. and it currently resides in the Museo del Prado in Madrid; it has been there since 1939. The way to read a triptych is by looking at the outside image first (when the panels are shut), then from left to right to unpack the story. So that’s what we’ll do.

The exterior panels show an image of the world during creation, most likely on the third day. This is in reference to Genesis 1:7, which states “God made the dome and separated the waters that were under the dome from the waters that were above the dome.” In the top left-hand corner is God himself, whose hands are raised (which was art-code for a person speaking), and across the top is an inscription that reads “Ipse dīxit, et facta sunt: ipse mandāvit, et creāta sunt,” which is from Psalm 33, and translates to “For he spoke and it was done; he commanded, and it stood fast.” There is no life on this planet, and it is noticeably devoid of color. We can see, however, the presence of vegetation, but no human life. When we open the panels, though, this all changes. I’ll show you the painting as a whole before we start to take a closer look.

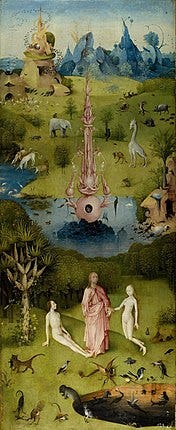

As you can see, there is a lot going on. Let’s start with the left panel to break down the “opening” scene.

The main focal point is in the foreground; God, in the form of Jesus, is giving Eve to Adam, the first man and woman. There are no other humans in this panel, but there are a lot of creatures and organic-looking structures. But I didn’t draw you in to talk about shapes; I want to focus on the creatures and their development over the three panels. We can see some animals that would be considered exotic to people during the Renaissance, like a giraffe, a monkey, an elephant, and a lion, but also many creatures that simply do not exist. There is a unicorn drinking from a watering hole alongside buffalo and other large animals, a three-headed bird heading to a pond on the ground near Adam, and odd amphibious creatures emerging from the water in the center of the painting. The presence of owls, like the one in the center of the fountain, is typically a symbol of a demonic presence, something that is definitely explored later in the painting. The creatures here are small and could be considered juvenile. There is a lot of debate over what they symbolize, or if they are just a product of Bosch’s trauma, but the overarching consensus is that they represent the corruption of humanity, leading them on the path toward sin. We can see this more in the center panel.

I can’t talk about the creatures in this panel without first addressing the humans. This panel, in contrast to the left panel, is dominated by human imagery. The humans here are engaging in explicit, sexual acts “overtly and without shame,” as described by art historian Walter S. Gibson. Human nudity is portrayed in every way possible, and the presence of fruit is also overtly sexual in nature. This panel clearly illustrates the title of the painting; it is truly a garden full of earthly delights, meaning sexual pleasure. In the Catholic Church, especially during the Renaissance, non-procreative sex was seen as extremely sinful and could get one ostracized from their community. This is not a worry for the humans in Bosch’s garden. There are a lot more, larger creatures, seemingly more mature than those in the left panel. There are gigantic ducks, large fish, camels, and a lot of bird imagery. The unicorn is again depicted in the background, this time being ridden by a man around the watering hole. There are some human-animal fusions, like the presence of a knight with a dolphin tail. Overall, the creatures here are just as carefree as the humans but carry an ominous tone to them. The birds, particularly the owl, are watchful of the humans, keeping an eye on their sinful activities, and preparing the viewer for what is to come.

The right panel is vastly different from the two that came before. Visually, it is much darker, with the imagery of fire being broadcast in the background. This is Hell, a world where succumbing to temptation has led to evil and eternal damnation. The results of the humans’ activities in the center panel are shown here. There is a lot happening here, and a lot more creatures. The focal point of the center is on the “Tree-Man,” who has a cave-like torso propped up on stumpy tree trunk arms. The creatures dominate this panel, unlike the previous two. The animals are punishing the humans, subjecting them to torture symbolizing the seven deadly sins. On the right, there is a large, bird-headed creature seated on a throne, devouring a human and defecating the corpses. He is sometimes referred to as “The Prince of Hell,” because of his regal stature on the throne, and the crown-like cauldron on his head. Left of the Prince is a demonic-looking choir master who sits between the large instruments and tattoos music notes on a human’s ass. The music notes have been transcribed and played, which I will link here in case you want to give this eerie tune a listen. There is a giant pair of ears with a blade between them, dogs and rabbits on the hunt for a human, birds with humans as slaves, and many other demonic creatures. Throughout the entirety of this painting, it is evident that it serves as a warning of the consequences of sin and eternal damnation.

The creatures in this painting are so stereotypically Bosch; in fact, it’s one way to pick his work out of a lineup. In many of his other works, there are weird-looking creatures, partly human, partly animal, that are in all sorts of scenarios. Bosch is widely considered one of the earliest surrealist painters, and was a major source of inspiration for many surrealist artists, like Salvador Dali. The Garden of Earthly Delights narrates a sense of sinful humanity, completely free of human restraint. This is why his creatures are such an integral part of the storytelling of the piece. Other little gremlin-esque creatures were popular in art at the time, like gargoyles. Gargoyles were on almost every church during the Renaissance, left over from the Middle Ages. Bestiaries were also common; they were illuminated books used to teach about sinfulness and morality, decorated with images of exotic animals discovered by explorers and fanciful, non-existent creatures, like dragons and unicorns. It was becoming an artistic trend to depict horrific creatures in Hellish landscapes as a sort of warning for what would happen to you if you were to commit a sinful act. They were especially effective for the majority of the community who were not literate so that instead of reading about what would happen to them, they could visualize it.

Notice how I’m not calling them “monsters;” I don’t believe they are. They are pieces of an artist’s imagination (in this case Bosch’s) that come together to create a narrative about humanity, through grotesquely non-human ways. In a way, we can all relate to being one of Bosch’s creatures; primal, immoral, and sinful. It’s a part of all of us, that, in the Catholic tradition, is a result of Eve’s Original Sin. These creatures are a reflection of humanity so we are forced to look at our actions and judge them as if they were not our own.

I drew a lot of my information that I didn’t get from the video essay (which wasn;t much, if I’m being honest) from the Wikipedia articles for Hieronymus Bosch and The Garden of Earthly Delights, so give those a read if you want.

As for media recommendations, I’ve really been into this art history thing, but if you made it this far, I won’t bore you with more video essay recommendations. Instead, I want to recommend Lizzy McAlpine’s Tiny Desk Concert, which is extraordinary. I think I’ve watched it at least 10 times within the past week.